How to fix your project collaboration model?

I've been studying the collaboration processes of the Apache Software Foundation (ASF) for a while [1], by observing and practicing the successful collaboration model that we use in ASF projects.

Taking the opposite angle, I've been reflecting lately on how to fix a broken collaboration model. How do you help teams move from an "I have no idea what my colleagues are doing, and I get way too much email" model to the efficient self-service information flow that we see in ASF and other open source projects?

As I see it, the success of the Apache collaboration model is based on six guiding principles:

- If it didn't happen on the dev list, it didn't happen.

- Code speaks louder than words.

- Whatever you're working on, it must be backed by an issue in the tracker.

- If your file is not in subversion it doesn't exist.

- Every important piece of information has a permanent URL.

- Email is where information goes to die.

Some of those might need to be slightly tweaked for your particular context, but I believe you can apply most of them to all collaborative projects, as opposed to just software development.

The context of an ASF project is a loose group of software developers, architects, testers, release managers and users (with many people playing several of these roles) working remotely, with no central decision authority. There's no manager in an ASF project, no money exchanged and no common corporate culture. Decisions are made by consensus, by a group that grows organically as new members are elected based on their merit with respect to that particular project.

This may sound like a recipe for failure, yet many of our projects are very successful in delivering great software consistently. How does that work?

Let's describe our six principles in more detail, so that you can see if they apply to your own project.

If it didn't happen on the dev list, it didn't happen.

In an ASF project, all decisions are made on a single developers mailing list.

Backchannel discussions are inevitable: someone will meet a coworker at the coffee machine, people attend conferences, talk on IRC, etc. There's nothing wrong with that, but the rule is that as soon as a discussion turns into something that has impact on the project, it must come back to the dev list. The goal is for all project participants to have the same information from a single source.

As those lists are archived, you can then go back to check why and how a particular decision was made.

Creating consensus using email only can be hard, on the other hand it forces you to clarify your ideas and express them in an understandable way, which in the case of software often promotes cleaner architectures and designs (but see also code speaks louder than words below).

Email etiquette (solid and evolving subject lines, concise writing, precise quoting etc.) plays a big role in making this work, and that's something people have to learn.

In an ASF project, experienced members will often help beginners improve their list communications skills, by gently steering them towards more efficient writing and messaging styles. And your message might just be ignored if the subject line says "URGENT: need help!" or "Question", which can be a good beginner's lesson.

Top-posting is usually frowned upon on ASF lists, as that often leads to superficial discussions compared to the much more precise inline quoting.

Email is where information goes to die.

Aren't we contradicting the previous principle here?

Not really - the dev list is for the flow of discussions and decisions, not for important information that people need to refer to in their work.

Even with good and multiple email archives like the ones we have for ASF projects, finding a specific piece of information in email is painful. That might be good enough for going back to a discussion to get more context about what happened, and to go back to decisions (marked by [VOTE] in their subject lines at the ASF) from time to time, but definitely not for the day-to-day information that you need in such a project. That's where the issue tracker, discussed below, comes into play.

Code speaks louder than words.

No one told me that when I started working in ASF projects, but after some time trying to argue about software architecture and how my ideas would improve our project's software, I realized that I was just wasting my time.

The best way to express a software architecture or an idea that will improve a software component is to implement it and show the code to your fellow project members.

That code might be just a rough and ugly prototype in any suitable programming language, that's not a problem - as long as it expresses your ideas, you will often spend much less time getting that idea across when it's backed by a concrete piece of code.

Whatever you're working on, it must be backed by an issue in the tracker.

This might be the most important of our guiding principles - on a desert island, I think I'd be ready to work with just an issue tracker as my collaboration channel.

Many people think that issue trackers are only for bugs: you create an issue when you have run your software and found something that doesn't work.

Although that was the original intention, I believe (and I've seen this fly in many different contexts) that an issue tracker can be used to back all the work that's being done in a software or other project. Software design, implementation, test servers and continuous integration setups and maintenance, hardware upgrades, password reset requests, milestones like demos and sprints (as issues, not just dates)...and bugs of course: managing all project tasks in a single tracker makes a huge difference.

When used as your coordination backbone, a good issue tracker (we currently use JIRA and Bugzilla at the ASF) will help answer a lot of questions about your project's status, such as

- Who's working on what?

- What did Joe Developer do last month?

- Where do we stand?

- What prevents X from being implemented?

- Why did we implement X in this way back in 2001?

For this to work, project members need to update their issues often, and break them down into smaller issues as needed, so that the tracker later tells the story of how the task went from A to B.

No need for big literary statements, but instead of sending an email to the dev list saying that X is ready to be used, just update the corresponding issue in the tracker. A good tracker will send events when that happens, to which people can subscribe. Together with the source code control system events (commits etc.) this creates a live activity stream for your project. Making extensive use of the tracker will help provide a complete picture of what's happening, in that stream.

I'm also a big fan of using issue dependencies to organize issues in trees that can be used to keep track of what needs to be done to reach the project's goals (aka "planning", but in a more organic form).

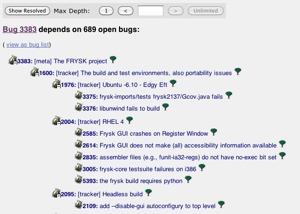

As an example, here's the dependency tree for bug 3383 of the cygwin project. That's not an ASF project, which shows that we're not the only ones to use this technique.

As an example, here's the dependency tree for bug 3383 of the cygwin project. That's not an ASF project, which shows that we're not the only ones to use this technique.

That tree starts with "the FRYSK project" as an umbrella issue, which is broken down into issues that represent the different project areas, and so on util it reaches the actual things that need to be implemented or fixed. Combined with a tracker's reporting functions, such a tree helps tremendously in answering the "where do we stand?" question, and in reshuffling priorities quickly in a crisis. You can also create umbrella issues for sprints or releases, to express what needs to be done to get there.

If your file is not in subversion it doesn't exist.

The goal here is to avoid relevant files floating around - put everything in subversion, or in whatever source code control system you're using.

If some files are really too large for that, make sure they have permanent URLs, and document those in the issue tracker or in your source code.

Every important piece of information has a permanent URL.

If you cannot point to a piece of information with a URL, it's probably not worth much. Or you're using the wrong system to store that information.

I also like to speak in URLs as much as possible. Saying SLING-505 (which is an agreed upon shortcut for https://issues.apache.org/jira/browse/SLING-550 in an ASF project) is so much more precise than referring to the background servlets feature.

Conclusion

Reviewing your collaboration model against the above principles should help find out where it can be improved. The most common problems that I've seen in the various organizations that I worked for in my career are the "split brain" problem, where testers, customers or managers use different tracking systems, and the "way too much email" problem where people send important information (or code...aaaaarghhhh) around in email as opposed to taking advantage of a tracker.

Does that sound like you? If yes you might want to have a closer look at how successful open projects work, and take inspiration from them.

[1] See previous posts: What makes Apache tick? and Open Source collaboration tools are good for you!.